This idea which I've blogged about previously was worked into a bid for a British Library Labs competition. My submission was unsuccessful but here's where I'm up to for another date. This article is therefore a "how it would be done" proposal.

I'm also aware I've not updated this in nearly a year! More to come from my backlog, and a possible move to a new domain.

Question: How can very large collections of audio data be quickly and easily searched and catalogued?

Abstract

Computers, and especially the web, handle audio very badly. Images and video are the de facto web media formats, while browsing large amounts of audio data is still a chore. This project will develop a new shorthand for audio data, and rethink how we visualise and manage audio data in order to bring it up to speed with where images have been for years.

Audio files should have beautiful, semantically rich thumbnails that convey information about the sound within, communicating meaningful properties of the sounds, in order to allow quick comparison and evaluation of the salient points of a very large number of files. Some of these properties are:

- Duration

- Rough frequency content

- Type (music, audio recording, podcast, etc)

- Volume/dynamic range

They could be represented abstractly with things like:

- Shape

- Colour

- Opacity

- Pattern

- Small icons

An audio metadata format will be created or adapted to allow these thumbnails -- a server side process can generate the metadata, which a html5 canvas can interpret. This metadata can then be used directly to allow sorts and filters on audio data embedded within web pages, file browsers or other GUI elements.

How can this idea showcase audio content?

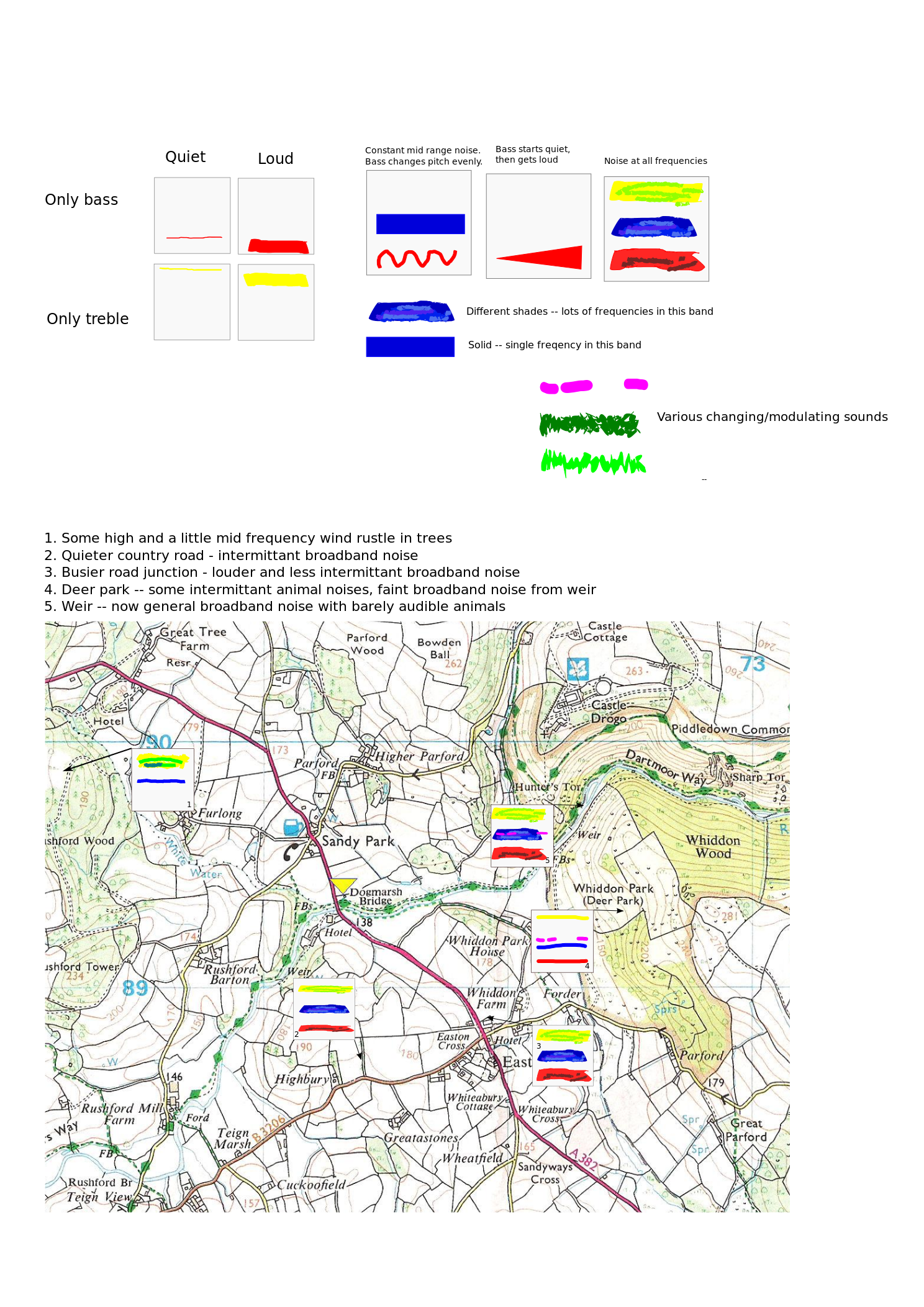

Audio data is very hard to effectively parse without directly listening to it, which is very slow for large quantities. Suppose I want to quickly find the short, bass-heavy, low-amplitude recordings on a web page or file browser. Without listening there is no way to do this. However, if amplitude is represented with height, frequency with colour and duration with width, then a thin, red rectangle could indicate the files I'm looking for. I can then compare other files -- a more orange rectangle might be a higher pitch, and a large blue square a long, loud, high pitched file.

Being able to ascertain basic properties in this way will hugely speed up interaction with audio.

Here are some examples of how I would process British Library content, with some very rough examples.

"Soundscapes" collection

There is already a map of soundscape recordings, and a separate XML database on the British Library website. However, reading the descriptions of each sound or seeing where they are located on the map gives little useful information about the data set as a whole. A useful visualisation here would be to directly superimpose sound glyphs onto the existing map. I've done a very rough mockup here, with some examples of how I would go about using the space. Click for a bigger view.

Ideally this should be rendered with a Google Maps/OpenStreetMap style pan and scroll interface, as is currently on the British Library website. This could be made into a complete sub-site, with extra controls for filtering based on volume, frequency content, duration, etc, using the metadata information. Straight away this output gives us rich contextual information about the sound environment, in ways that wouldn't necessarily be obvious from listening to sounds one at a time.

“Accents” collection

In a similar way, the “accents” collection has a huge amount of files but no practical way of discerning or identifying an accent heard in the real world short of listening to every file. A well designed glyph would show important parts of the audio recording, and may show where vowels or consonants are emphasised more. This application would necessitate a specialised application and analysis; however, likely focusing heavily on the freqency bands for vowels and consonants. Again, superimposed glyphs on the map may show interesting regional or national patterns that would be hard to discover or navigate with a manual listening exercise.

Similar experiments with manual coding show fascinating results, for example Joshua Katz's “Dialect Survey Maps”. Imagine a map like this with sound recordings layered on top!

Birdsong database

Ascertaining a birdsong in the wild can be very difficult. Some birds are known to imitate others, and the songs can be very similar. This is another example of a specialised application: with birdsong we are only interested in a fairly specific, high pitched section of the frequency range.An ideal thumbnail here would show the pattern and pitch of each bird, in a much more literal way than the general soundscape recordings. A simple thumbnail list with filters is the best visualisation here -- there is no need for map data. Through listening to a bird in your garden, the thumbnails would allow you to vastly narrow down the number of recordings to compare the birdsong with. With filters for, for instance, geographical region and rarity, a well designed format should point you to relevant files very quickly. Again, to reiterate the project goals -- the thumbnails are an aid to focussed listening, not a replacement for listening.

My research

I have about 400 audio recordings from my PhD fieldwork of people's day-to-day lives, with associated log book entries for what they were and what people thought about them. Without cross-referencing a large spreadsheet, there is no way for me to tell the content of the files without listening to them all. Suppose I want to find audio files that consist of broadband noise, in order to compare responses to them -- there is currently no way of doing this without resorting to one of the above solutions. I have metadata for all the sounds the person heard in the recording -- if I could select, say, all recordings of traffic and compare the thumbnails to see the range of experience here, it would greatly assist my critical comparison skills.How would this be implemented?

The basic framework would be:

- Research existing audio meta data formats.

- Talk to people who access the audio collection to establish user stories about what they need, how, and when.

- Work with an artist to develop an intuitive prototype visual shorthand.

- See if there is an existing server-side program to generate the metadata -- if not, work with a developer to generate one.

- Create a proof-of-concept jQuery plugin that implements all this given an input of audio files and their corrosponding metadata.

Potential public engagement -- Sounding Shapes

Members of the public will be shown shapes of different sizes and colours, and asked what they think they sound like. They will be played sounds (on headphones) and asked to draw them. This will be a fun, portable public engagement, on the net and other sites as available.

After collecting the data we can publish the results and see what similarities and differences there are between both the ways people draw sounds, and describe the sounds of drawings. This will hopefully be a fun, viral project that can potentially get some traction with the Sound Art community, local news, and blogs on web and interactivity.

Thanks to Amanda for letting me know about the competition, and everyone who gave feedback on my proposal.